Hoboken is home to over 60,000 residents packed within the city’s square mile footprint. During peak hurricane season in the fall, however, those who call Hoboken home are plagued with incomprehensible flooding. This water is frequently a mixture of rainwater and sewer backup. It covers the streets of Hoboken without fail every autumn. Hoboken’s flooding problem goes back hundreds of years to its initial settling, but lately, lawmakers are looking to curb the issue as much as possible.

Why Hoboken Floods

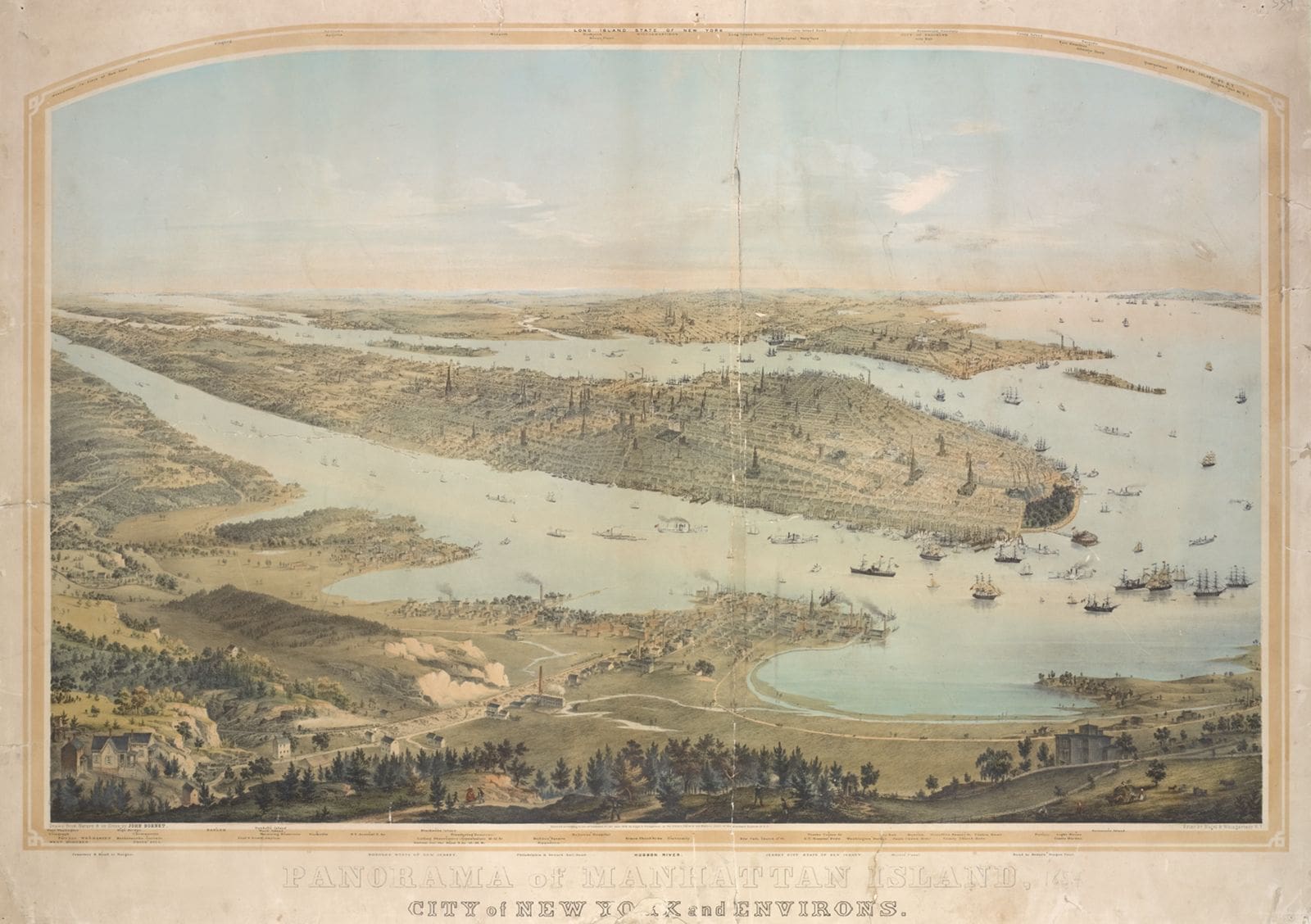

Two main factors contribute to Hoboken’s flooding problem: the geology of the surrounding area and how the urban area was developed. Prior to the settlement of what is known today as Hoboken, the area was primarily composed of tidal marshes. A tidal marsh—or wetland—is an area of land that is either constantly or partially flooded due to a change in the ocean’s tides. These wetlands are pervasive across the New York City metropolitan area, and one of their most important functions involves rainwater.

As rain falls across a given area, it will begin to collect and funnel into the local river system. During heavy rainfall, a large amount of water can enter a river and cause it to flood. Wetlands help to slowly release rainwater into the river system to prevent this flooding. The problems arise when these wetlands are filled in and developed, as was the case in Hoboken. When marshes are paved over with impervious materials like concrete or asphalt, the water is unable to infiltrate the ground. Instead, it inundates the municipal drainage system, potentially overloading it and causing local flooding.

Hoboken’s Flooding is Historic

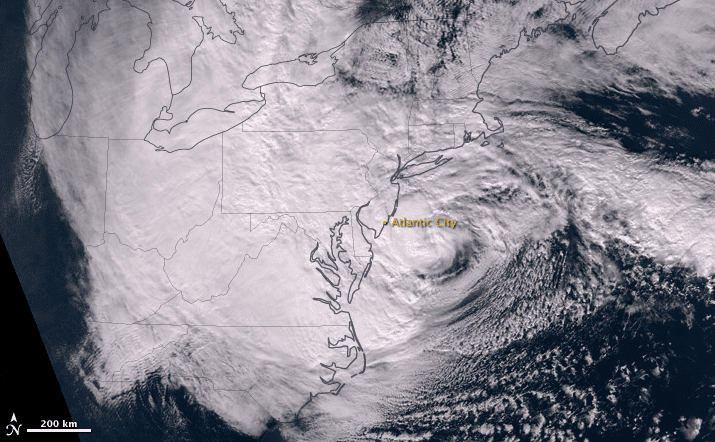

Hurricane Sandy battered the East Coast in October 2012. The storm careened through 24 states and saw a maximum wind speed of 115 miles per hour. Of the countless communities ravaged by the storm, Hoboken saw excessive flooding, with rising waters being pervasive and impregnable for much of the south side of the city. The streets of Hoboken were flooded with 500 million gallons of water from storm surge as per some estimates, and the National Guard was deployed in the city on October 31.

Almost a decade later, Hoboken saw even more historic flooding. This came during the peak of hurricane season with a sucker punch from two massive storms. Hurricane Henri crushed the Mile Square in August 2021 with four inches of rain in a four-hour period. All of which accumulated in the streets of the city. In September, Hurricane Ida dumped sheets of rainwater across the tri-state area. With a maximum flux of 3.24 inches of rain per hour at the storm’s peak, Hurricane Ida resulted in 11 deaths in New Jersey—most of which were flood-related. Later in October, a nor’easter closed out the hurricane season with violent winds and intense rainfall in the New York City metropolitan area. It later moved on to wreak havoc in Massachusetts.

Hoboken’s Climate Resiliency Plan

As a result of Hoboken’s dramatic flooding over the last 10 years, the local government is beginning to realize the threat posed against the Mile Square. Hoboken received a $230 million grant in 2014 from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to develop a climate resiliency plan. The plan includes the separation of Hoboken’s sewer system into a sanitation system and stormwater to aid in flood management, and the construction of over 9,000 feet of flood walls.

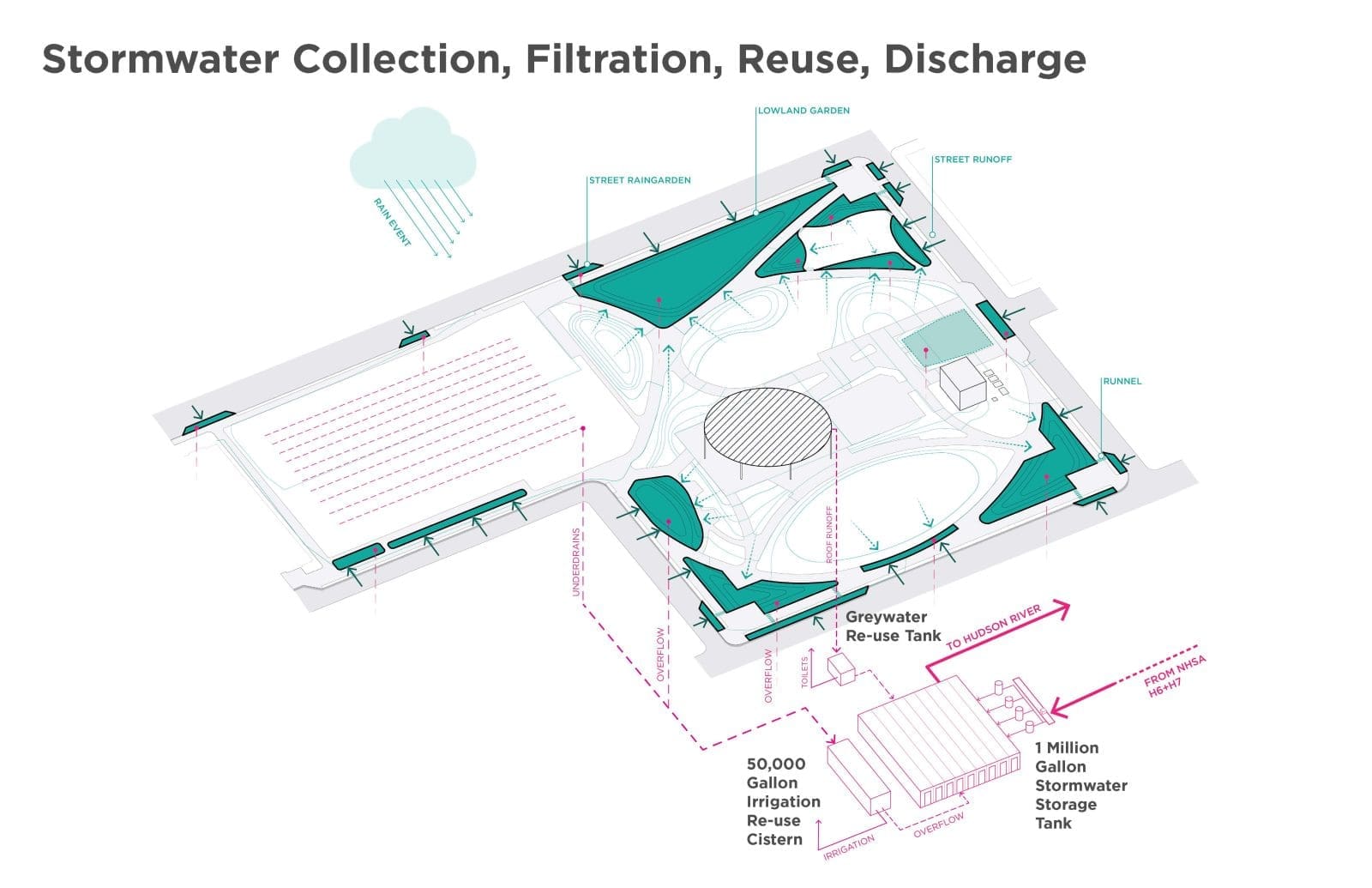

Another project aimed at curbing Hoboken’s flooding pandemic is the Northwest Resiliency Park. It will be constructed between Madison and Adams Streets and 14th and 11th Street. The plan to develop the empty lot in the area has been on the table since 2004. In 2014, the site was recognized by the municipal government as a potential location for green infrastructure. The City of Hoboken bought the lot in 2016 for development.

On the surface, the park is just like any other. There’s a multipurpose athletic field, pavilion, and grassy knolls covering the three-block area. However, underneath the park is an extensive network of pipes and tanks. They are designed to help pump away stormwater from flooding events, filter the water, and redirect it into the Hudson River. The park is the first of many green infrastructure projects Hoboken is developing with the hope of curbing the inconvenient—and sometimes deadly—aftermath of flooding in Hoboken.

What’s your opinion on the flooding in Hoboken? Let us know in the comments.

I'm a scientist obsessed with New Jersey's environment and geology. I'm probably reading science fiction. Or watering my plants.

- Kevin Hurlerhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/khurler/

- Kevin Hurlerhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/khurler/

- Kevin Hurlerhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/khurler/

- Kevin Hurlerhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/khurler/