At June in Collingswood, NJ, diners are treated to the heights of French cooking, including one preparation only available in some of the world’s most notable restaurants.

If there is one thing to know about French cuisine—or, at least the cuisine enjoyed by the elite of France throughout its history—it’s that it is absolutely not shy. Before the rich in France decided that food could use an upgrade, dishes were very one-dimensional. At the end of the day, food was simply a fuel that kept you alive. That was until François Pierre de la Varenne published a cookbook titled “Le Cuisinier François” in 1651. The writings proposed a shift from heavy, one-sided cooking to more modest preparation that emphasized high-quality ingredients (and let’s not forget a way to show off the fancy new foods that the French elite stole from colonized territories).

The Evolution of Haute Cuisine

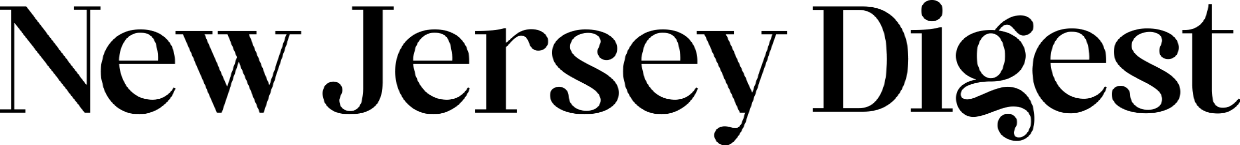

In the early 19th Century, a pastry chef by the name of Antonin Carême published “Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien,” which contained recipes meant to be prepared by skilled pastry chefs.

Along with his other published pieces, Carême’s books included sketches of grand pastry displays—something that could serve as a centerpiece for a gathering or a banquet. After all, by this point, food was as much a work of art as it was fuel for the bourgeoisie.

La Varenne and Carême established the modern cooking that would remain prevalent for the next 300 years—planting the idea that France should be seen as the center of the culinary universe. This style of cooking—one which focused on premium ingredients carefully garnered by skilled workers for the elite—became known as Haute Cuisine. Jules Gouffé and Urbain Dubois were other notable culinary revolutionaries of the time.

The Early Days of Canard à la Presse

Around this time, one chef named Machenet created a device that would eventually become the centerpiece of a culinary presentation that was more flashy than anything before it: The duck press. The idea was that they would press duck carcasses tableside and produce a sauce from the animal’s own blood.

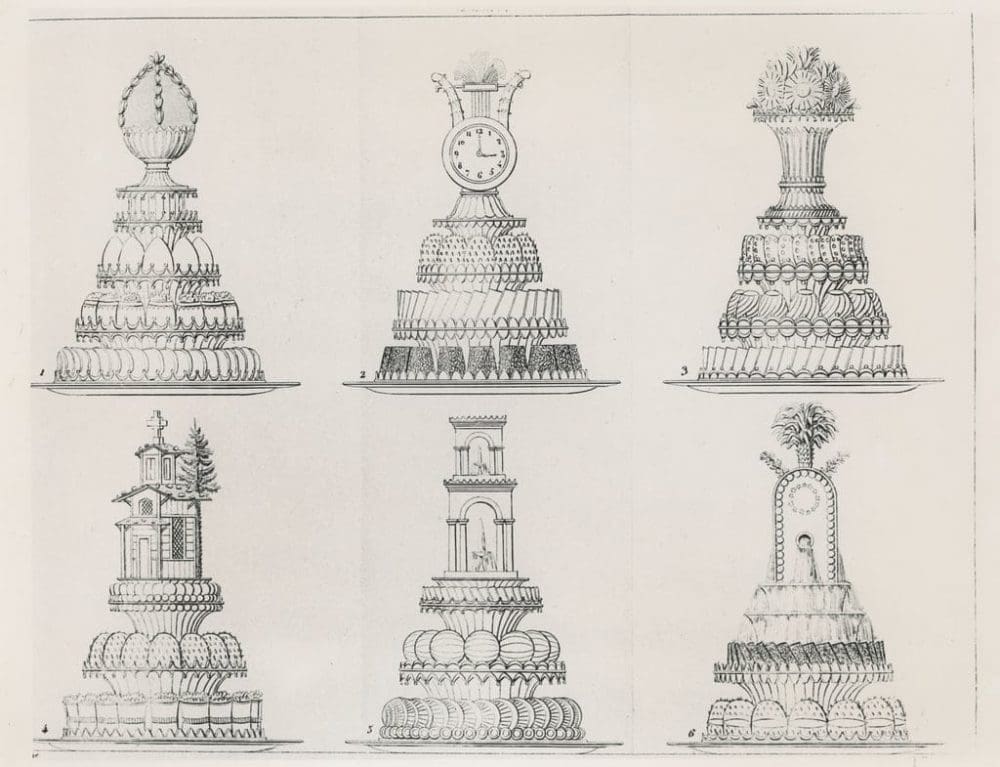

This really took off when Chef Frèdèric adopted it at the Paris restaurant La Tour d’Argent as the eatery’s staple offering, establishing what many consider to be the peak of French cooking: Canard à la Rouennaise—or duck in blood sauce. The meal would involve a whole-roasted duck, which was presented and carved tableside. The carcass would then be loaded into a metal contraption, brandished with luxurious design and, most notably, a hand-crank. A server would then twist the wheel, crushing the carcass and releasing the juices and blood. This mixture would be used as the base of a sauce. La Tour d’Argent still serves the dish to this day. Canard à la Rouennaise became popularized in England during the early 1900s when London’s one percent was desperate to feel as high-class as the French elite. The legendary Chef Escoffier, who is considered the mastermind behind the kitchen brigade system, served it at his London restaurant The Savoy. Over time, it became more commonly known as Canard à la Presse, or pressed duck in English.

I have been fascinated by this dish ever since watching Action Bronson enjoy it at NYC’s Daniel in a Munchies video seven years ago. For a young, aspiring cook at the time, it was a mesmerizing process and something that I would dream of one day trying. However, its scarcity made it hard to obtain, and I was certifiably broke. Fast forward to two months ago, when I discovered that a New Jersey restaurant is showcasing pressed duck on its menu—making it one of a handful of restaurants in the US that offers the gruesomely beautiful preparation.

I had to have it.

June BYOB

Walk into June in Collingswood, NJ on any given night and you’ll see the likes of beef Wellington, escargot and, yes, a server cranking a duck press tableside. These are all sights that fit well with June’s classically French interior, which features white tablecloths, leather-backed chairs, copper pots and plenty of elegant light fixtures. The BYOB is run by husband and wife duo Richard and Christina Cusack. Richard is the Executive Chef of June, while Christina is an experienced front-of-house mind and certified sommelier.

Chef Cusack bounced around famous kitchens, including Daniel, Le Bec Fin and several Michelin-starred restaurants in Paris. His love for upscale cuisine eventually led him to open June in 2019. Originally in Philadelphia, June moved to Collingswood in 2021. Cusack’s flagship restaurant has made headlines for its classic yet inventive take on French cooking. For Cusack, it felt as if June would not be complete without the most grandiose preparation in all of upscale dining. And as such, Canard à la Presse found its way onto the menu.

The Pressed Duck is in addition to a well-rounded a-la-carte menu and a five-course Chef’s Tasting—all of which have received glowing reviews.

The Pressed Duck at June

The meal begins quite typically with an amuse bouche. The night I dined, it was a black truffle and lobster soup. The velvety soup boasted sweet flavors of lobster and fish stock, emboldened by the presence of black truffle, which rather than overpowering the delicate flavors, accentuated them. I am not one to like something simply because it has truffle in it, nor is it ever an ingredient I order by choice to be quite honest; however, Chef Cusack’s execution was utterly remarkable. It was an over-the-top first bite (or sip) that perfectly guided me into the pearly gates of what was to come.

When you make a reservation at June, you have to specify with an email if you would like to do pressed duck. This is because a whole duck is reserved for each Duck à la Presse, which is aimed to serve two people.

And though the star of the meal is the duck breast, you are treated to the legs as well during the initial course. A plate of one of my absolute favorites, duck confit, was placed before me. The confit process involves curing duck legs for at least a day before gently cooking the meat in duck fat. There are several directions to take it from here—you can cool and shred it to be used as a piece of a larger charcuterie board, pot it with its own fat and spread it on crackers, or present it as a tangible dish, where the whole leg is the centerpiece. June opts for the latter.

The fall-apart duck leg is finished at a high heat to crisp the skin and just warm the meat through. Chef Cusack plates it alongside a simple salad and roast potatoes, with a foie gras parfait to accompany it. The rich offering plays with your taste buds in the best of ways. The foie gras acts as a butter, easily spread atop the duck where it slowly melts into each crevice of the meat. Don’t overlook the salad, though, as the crisp arugula and simple lemon vinaigrette is wholly necessary to cut the fat of the other components. I found myself enjoying this course almost too much—spreading the foie gras on slices of crusty bread and topping it with torn pieces of shatteringly-crisp duck skin before shoving the creation into my mouth with my fingers. Not exactly the way that the French elite might have pictured it.

The foie parfait was especially delicious with a mind-blowingly smooth and buttery texture. Luckily, more of it was to come.

With perfect pacing, our server Saverio rolled the duck press cart over to the table which involved the duck press itself and a stovetop with a copper pot. Minutes later, the roasted duck breast was presented to us. Saverio explained that the breast is marinated in red wine for two days and then seared in the oven just to brown the skin, but the meat is left virtually raw. He then carves the breast off the carcass and heats a copper pot with butter and hard herbs. The breasts are seared skin side down in the hot butter and finished at medium rare. Meanwhile, the carcass is cut with shears into pieces and loaded into the press.

Saverio asked us if we would like to crank the press, which we did with glee. This was a beautiful touch as it worked to make what is historically an inaccessible dish feel more casual and fun. So, you turn and turn and turn the wheel that is atop the press until, eventually, you hear a crack. Then, several more cracks. The bones, their marrow and anything else attached to the carcass become crushed, spilling their juices out of a spout at the front of the device and into a small copper pot. It’s primal, really, but it connects you to your food in a way that few other preparations can.

Saverio then brings the juices to the stovetop—by now, the duck is finished cooking and resting on the cutting board. A disk of foie gras parfait is melted in the pot, which is decorated with plenty of delicious duck fond and brown butter by this point. The foie melts and the pressed duck juices are emulsified into it. To finish, cognac is swirled into the sauce and lit on fire—a process known as flambé. The ignition illuminates the dining room, turning heads in the process.

Saverio then seamlessly sliced the rested duck breast and fanned it on a plate with oakwood mushrooms, finely chopped lacinato kale and fresh tiger figs. Of course, the accompaniments change seasonally. The sauce is spooned over the duck, blanketing each morsel of mid-rare meat—he leaves the excess sauce on the side if you feel you need more.

Finally, after seven years since my first exposure to pressed duck, it was all mine. I carefully lifted a piece of the glistening meat to my mouth and reveled in what was one of the most special bites of food in my life. This went beyond flavor. For me, it was deeply personal.

If you know French cooking, it’s all about the sauce and that is no exception at June. The à la presse sauce was rich, sticky and incredibly bold with the addition of cognac. Is it really a “blood sauce” as Frèdèric called it at La Tour d’Argent all those years ago? Well, it depends how you want to look at it, I suppose. The sauce does not have a blood taste, or appearance and I prefer to just think of it as no different than using the drippings from a roast to make a gravy. Albeit, the process of pressing the carcass yields a far richer dripping.

The duck skin was crisp and rendered, while the flesh was well-seasoned from the red wine. The vegetables and fruit which accompanied the meat were excellent as well. The mushrooms and kale were ideal vessels to soak up all of the excess sauce on the plate, while the tiger figs were sliced in half and brilliantly left as is. It’s sort of what haute cuisine is all about, taking an ingredient as wonderful as an in-season fig, and presenting it in the best way the chef can think of—in this case, raw. I found taking a bite of duck and fig together as the best way to enjoy the dish.

I finished my last bites of duck, closing the book on what was, unbeknownst to the staff or chef, a years-long journey for myself. But, the meal was not complete yet—there was still dessert.

The Pressed Duck meal always finishes at June with another haute classic, Crêpes Suzette. Crêpes are cooked and sauced in a caramel made from butter, sugar, orange juice and orange zest. A scoop of vanilla bean ice cream is served alongside the crepes, which are adorned with orange supremes and Grand Marnier tableside before Saverio ignites it in what is the second flambé of the meal.

This is one of my all-time favorite desserts and June’s was right up there with some of the best I’ve had. I especially loved the flavor of Grand Marnier which is apparent in every bite of the crêpe. Combined with the smoothness of the creamy and sweet ice cream, the crêpes were the perfect way to end what is a truly unique dining experience.

June offers excellence in its menu. Whether you choose to dine a la carte, Chef’s Tasting, or as I recommend with the Canard à la Presse Voyage, you are treated to an elegance rarely found in New Jersey restaurants. It isn’t the current culinary fad or the over-the-top gimmicks found on social media, but it is a dining journey that has stood the test of time. After all these years, there is a reason restaurants in Paris and beyond serve this delicacy, and there is even more of a reason why people travel to try it.

If you are in New Jersey or Philadelphia and enjoy partaking in the finer side of dining from time to time, you owe it to yourself to book the Canard à la Presse Voyage at June in Collingswood, New Jersey. It is, without a doubt, one of the Garden State’s greatest culinary treasures.

Peter Candia is the Food + Drink Editor at New Jersey Digest. A graduate of The Culinary Institute of America, Peter found a passion for writing midway through school and never looked back. He is a former line cook, server and bartender at top-rated restaurants in the tri-state area. In addition to food, Peter enjoys politics, music, sports and anything New Jersey.

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/