It’s something entirely trivial, but don’t you think it’s a tad strange that we call the meat from a cow “beef” instead of simply “cow?” Same goes for “pork” versus “pig” and a slew of other meat names that don’t match their animal counterpart. Many think this is to mentally distance ourselves from the idea that we are eating a slaughtered animal, but that’s not entirely true either. After all, chicken, lamb and other meats are called what they are. There’s no distance there.

So, how did we get to this point? When you sit down and have a steak dinner, why are you eating beef and not cow? Well, you can thank the French, or more specifically, the Normans.

The Norman Conquest

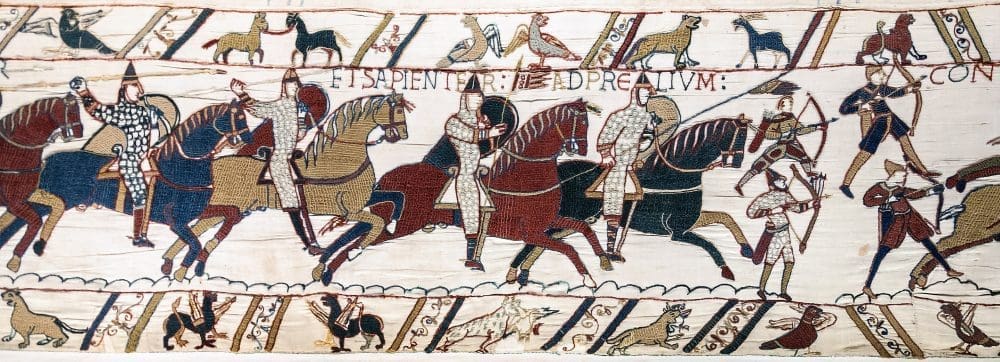

It’s the 11th century, and a world-shaping event is about to go down— the Norman Conquest, or simply the Conquest. During this period, England was invaded and subsequently controlled by a coalition of forces including Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French soldiers. These troops were under the leadership of the Duke of Normandy, who would later come to be known as William the Conqueror.

The Normans didn’t just wake up one day and decide to slaughter the English. Instead, William had a particular interest in England, as their newly crowned ruler, Harold Godwinson (also known as Harold II) crowned himself king of England following the death of his brother-in-law and King, Edward the Confessor—who died without an heir. Harold II rushed his coronation and little did he know it at the time, but he would become the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. The problem was this: The crown was owed to William, the Duke of Normandy, or at least he felt it was—thus, pushing William the Conqueror to, well, attempt to conquer England. It was official, William and Harold had…beef.

In 1066, William the Conqueror began his invasion of England, crossing the English Channel with thousands of troops. This began the Battle of Hastings in the fall of 1066. On England’s side was Harold II’s army, which was large but consisted mostly of foot soldiers. On Normandy’s (the French) side, was William’s army which was about equal in size to Harold’s, albeit far more advanced in combat. This battle resulted in Harold II’s death. The Normans were officially in.

England’s Norman Shift

Following the Battle of Hastings, William went on a campaign through a rebelling England, slowly converting each corner of the country to Norman. Over time, English nobles were replaced with Normans, buildings (such as the Tower of London) were built with Norman/French architecture, French became the language of the elite and with it, the English language itself began to transform.

The Transformation of the English Language

The Normans brought their unique dialect of French to England and it melded with the English language, creating what we know today as “Anglo-Norman.” This created dichotomies within everyday speech such as “shirt” versus “blouse.” Even today, the words that we tend to think of as more upscale or posh are largely of Norman origin.

So, you probably can guess where this is going. You see, French nobles ate meat—a lot of meat—but they never had to slaughter the animals themselves. That’s peasant work. So, Normans had names for meat that differed from the animal, because to them, they were two separate things. As far as a noble was concerned, beef and poultry grew on trees. And because the French tend to be responsible for many culinary origins, the words for food that they brought over stuck.

The French word for cow meat, “bœuf,” became “beef” in the transformation of English and the word for pig meat, “porc,” became “pork.” Some of the language changes faded over time, but many stuck. Today, if a word sounds eerily similar to its French counterpart, you might be able to trace it back to William the Conqueror.

In fact, we owe much of written English to the Normans, as a majority of Anglo-Saxons could not read or write before William conquered the land, which is ironic because William himself could not read or write either.

It’s Beef, Not Cow

The Battle of Hastings had an unthinkable amount of influence on England and the English language, one of which is how we refer to many everyday foods. Though it isn’t that important in the grand scheme of things, beef, pork and veal sound a whole lot more elegant than saying cow, pig and baby cow. So, the next time you’re out for a steak dinner with friends or family, make sure they know why they’re munching on beef and not cow—we can thank William the Conqueror for that one.

Peter Candia is the Food + Drink Editor at New Jersey Digest. A graduate of The Culinary Institute of America, Peter found a passion for writing midway through school and never looked back. He is a former line cook, server and bartender at top-rated restaurants in the tri-state area. In addition to food, Peter enjoys politics, music, sports and anything New Jersey.

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/

- Peter Candiahttps://thedigestonline.com/author/petercandia/