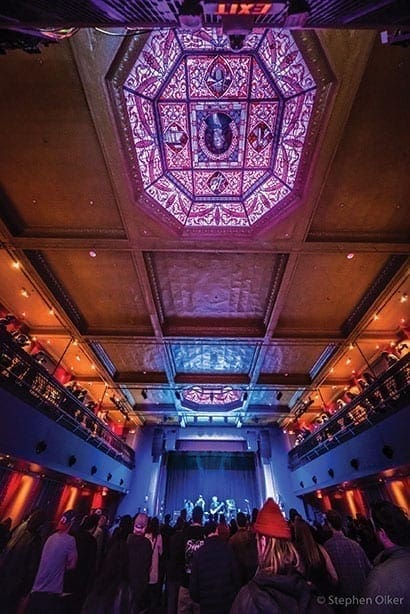

Photos by Stephen Olker

This spring, Ben LoPiccolo—owner of Ben LoPiccolo Development Group (BLDG)—and his team oversaw the reopening of White Eagle Hall (WEH) on Newark Ave in Jersey City, a venue that’s had its doors closed since 2003. The restoration of the hall not only pays homage to the building’s rich history by incorporating an intimate mix of the original building elements, but it helps fill a gap in the Jersey City music and theater scene.

WEH first opened its doors in 1910, after being constructed by Polish immigrants who came to the U.S. during the peak years of Ellis Island’s opperation. Ownership eventually transferred to St. Anthony’s Church during The Great Depression, who managed it as a community rental facility throughout the 20th century. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, local music promoters began holding events at the hall, including everything from dances and concerts to “battle of the bands” nights. Before long, WEH became well-known as a local Rock & Roll hotspot for young adults in Hudson County. Out of this short-lived music scene emerged talented individuals such as Frank Infante and his band World War III. Infante, a Jersey City-raised musician, became a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee as a guitarist for Blondie.

Although its brief music scene was prominent in the community, WEH’s most well-known contribution was to the sport of basketball. The hall was home to the Friars, the basketball team of St. Anthony High School coached by the legendary Jersey City-native Bob Hurley. Though official games never took place at WEH, the team used the facility for practices, and went on to win 23 state championships (a national record); they became famously known as the inner-city team without their own gym.

Although its brief music scene was prominent in the community, WEH’s most well-known contribution was to the sport of basketball. The hall was home to the Friars, the basketball team of St. Anthony High School coached by the legendary Jersey City-native Bob Hurley. Though official games never took place at WEH, the team used the facility for practices, and went on to win 23 state championships (a national record); they became famously known as the inner-city team without their own gym.

Though WEH would close its doors in 2003, LoPiccolo went on to purchase the property, with the original plan of starting a condo project. But around the same time, he began learning a great deal about theater and its positive impact on communities from his wife, Olga Levina, artistic director at Jersey City Theater Center. “I remember going home and telling Olga that I found a theater, but I just couldn’t tear it down and start putting in condos. “I really liked the architecture… the shape of the building, it is a perfectly balanced structure,” he explained. By [2004] the asking price was too expensive to make it work as a theater, so I left it.” But during the financial crisis in 2008, the prices halved, allowing LoPiccolo to make the numbers work for a theater, with two restaurants paying rent.

In 2010, LoPiccolo and his team began conducting structural engineering and environmental studies on the building in addition to demographic and marketing studies for creating a theater. Two years later the contract was signed and by 2013, they presented WEH’s plans to the community with an open house. “I first thought this would be one of my typical projects, where you do a lot of research but also do research as you build. But with [WEH], we soon realized that we needed to make the space very flexible to accommodate all the diverse programming we needed to.” In addition, the sound system and studio space needed to be optimized for music, but in such a way that the music would not disrupt the restaurants below but also still attract good bands and big names. This meant that the plans to renovate started to evolve as the project continued.

Because WEH was built in 1910, there were some obstacles to overcome during the restoration process. The structure could not sustain the infrastructure LoPiccolo and his team needed, which was 60 tons of concrete, leading them to adopt strategies unique to the structure’s situation. “The original foundation wasn’t built for that, or for the massive air conditioning units on the floor and our new speaker system. There was a lot of weight on the building. We literally had to start underpinning the whole structure.”

Pieces of the building’s storied past still remain today. The hall still adorns its iconic White Eagle, a symbol that has epitomized the Polish nation for over a thousand years. A small bust commemorating Jan Paderewski, a world-renowned pianist and composer who later became the Prime Minister of Poland, is chiseled into the building’s facade along with three other Polish notables. You can even see the original St. Anthony’s Bingo Game sign which still hangs near the WEH Newark Ave service entrance. Inside its charming interior, the original wood basketball floor that the Friars once practiced on was repurposed as bar counters and balcony flooring for the performance and bar area.

The completed space is 13,353 square feet, including over 5,000 square feet of ground level restaurant space for Cellar 335 and Madame Claude Bis. The performance space, which features the latest in lighting and sound tech, boasts 28-foot ceilings and can hold 400 persons seating and 800 standing, including a balcony level bordering the hall’s perimeter. But one of the most magnetic parts of WEH’s space are two stunning hand-crafted stained glass skylights – which immortalize Frédéric Chopin, a classical music composer, and Marcella Sembrich, an internationally recognized opera singer.

The completed space is 13,353 square feet, including over 5,000 square feet of ground level restaurant space for Cellar 335 and Madame Claude Bis. The performance space, which features the latest in lighting and sound tech, boasts 28-foot ceilings and can hold 400 persons seating and 800 standing, including a balcony level bordering the hall’s perimeter. But one of the most magnetic parts of WEH’s space are two stunning hand-crafted stained glass skylights – which immortalize Frédéric Chopin, a classical music composer, and Marcella Sembrich, an internationally recognized opera singer.

The hall officially opened on May 5th with a ribbon-cutting ceremony followed by a performance headlined by Rye Coalition, a Jersey City-based band, and has plans to feature other nationally known musicians. With two highly notable restaurants just downstairs, this new hotspot promises to deliver its patrons a full experience. “White Eagle Hall is a destination and people can play an entire night in one place. They can come for dinner at one of the restaurants, watch a show and have a drink [at WEH], which will also serve food, or go to a restaurant after the show. It’s literally a whole experience in one venue,” LoPiccolo added.

The details of a neighborhood’s development tells us a lot about what’s important to its people, and music and the arts continues to be the backbone of Jersey City’s culture. It’s clear this cultural boom is almost synonymous with the restoration and repurposing of buildings for today’s community. These spaces often come with a rich background and part of their restoration is about bringing their antiquity into 2017 and preserving their historical legacy.

Michael is the Editor-in-Chief of New Jersey Digest, COO of X Factor Media, and an avid fiction writer. A Bergen County native, he discovered his passion for words during a long stretch of Friday detentions. Michael loves kayaking, a fat glass of Nebbiolo, and over-editing.

- Michael Scivolihttps://thedigestonline.com/author/mscivoli/

- Michael Scivolihttps://thedigestonline.com/author/mscivoli/

- Michael Scivolihttps://thedigestonline.com/author/mscivoli/

- Michael Scivolihttps://thedigestonline.com/author/mscivoli/