“North, South, or Central?”… said nobody 300 years ago. Today, we use linguistic differences like the Taylor Ham-Pork Roll debate to draw the line or major highways like I-295 (personally, I say it’s I-78), but for a 28-year period, the question was whether you fell on East New Jersey or West New Jersey. The two were so separate that they had different governors and even different constitutions. Here’s a brief summary of the almost three decades that New Jersey was two different states.

Background

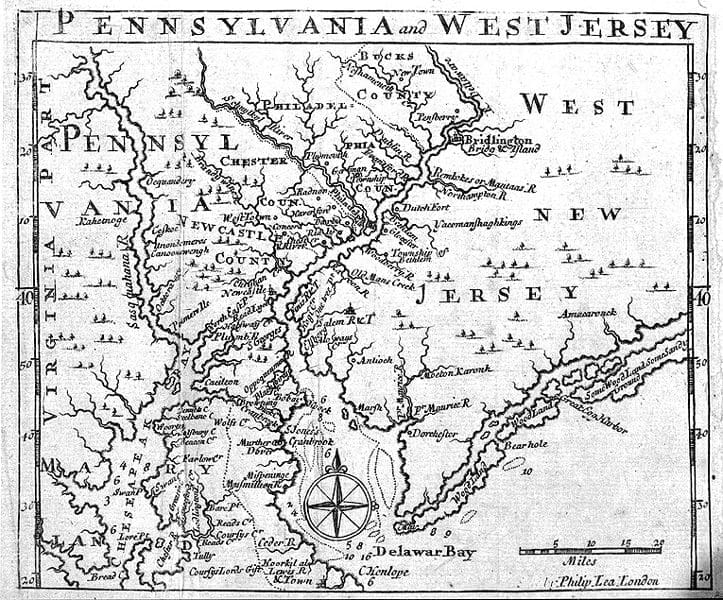

Following the Anglo-Dutch War over the region, the Province of New Jersey was granted to England in 1674. It was split into two distinct parts, East and West Jersey, governed by Sir George Carteret and Lord John Berkeley, respectively.

After a long line of the proprietors’ debts and subsequent property transfers, East and West Jersey called for the creation of a formal border. Several lines were proposed, all of which drew a diagonal starting at Little Egg Harbor going northwest. Lines were adjusted for settlers’ property boundaries.

East and West Jersey

East Jersey quickly organized itself into counties based on the seven main towns: Bergen (now Jersey City), Elizabethtown (Elizabeth), Newark, Woodbridge, Piscataqua (Piscataway), Shrewsbury, and Middletown. The resulting counties were Bergen, Essex, Middlesex, and Monmouth. Familiar names like Hacksack (Hackensack), Freehold, and Perth Amboy, which became the capital of East Jersey, also made their debut at this time. Somerset County was also created but was categorized as a township.

West Jersey wouldn’t officially form counties for a bit longer. Instead, they went by court jurisdictions. Proprietors divided all of West Jersey into tenths, possibly rooted in the province’s strong Quaker ties. The tenths were overseen by courts: Burlington, Gloucester, Salem, and Cape May. Sound familiar? They would eventually become counties, too.

Reunification

Property struggles heightened tensions as land owners, English authorities, and local residents fought over land. Royal decrees had to be sent out detailing the proprietors’ right to the soil. Eventually, proprietors in the East and West both forfeited their land to the crown, placing James Duke of York as the governor of both New Jersey and New York. At one point, it was even considered to cede West Jersey to Pennsylvania and East Jersey to New York, which may explain some cultural differences throughout modern-day NJ.

Legacy

Today, the earliest proposed line, the Keith Line, serves as the border between Burlington and Ocean counties, as well as Hunterdon and Somerset counties. The following border, the Coxe-Barclay Line, now denotes the border of Morris, Somerset, and Sussex counties. The border would be surveyed a few more times until the Lawrence Line was drawn in 1743 to clean up any remaining disputes.

One might even argue that dividing the state East and West still holds up better than North and South. As seen in a map of sports teams, fandoms fall eerily close to the borders drawn over 300 years ago. Linguistic boundaries are similar. Ultimately, it comes down to proximity to New York or Philly, and in that case, East and West seems to be the dominant divider, not North and South. But after all of this, should New Jersey have stayed two different states? I say no. The divide is what makes Jersey, well, Jersey. The need to argue with one another, that’s what makes us all from this great state.

Alex Kenney is a third-year Journalism and Media Studies student at Rutgers University - New Brunswick. Having lived in Bergen, Essex, and briefly Hudson County, she calls anything north of Newark home. She is a big fan of NJ Transit and knows most major highways in her area like the back of her hand, even though she doesn’t drive.

- Alex Kenneyhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/alexandriakenney/

- Alex Kenneyhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/alexandriakenney/

- Alex Kenneyhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/alexandriakenney/

- Alex Kenneyhttps://thedigestonline.com/author/alexandriakenney/